Back to the days when we first welcomed our robot, Bluefrog's Buddy the Robot, at our lab, my PI and me struggled to come up with a satisfying name for it. At the end, I was inspired by the nickname of my Ph.D supervisor's little son, Lulu. So I proposed Lou to my PI for our robot. Moreover, I supposed it's gender-neutral and help me observe how the colleagues will attribute roles to the robot.

But I was so wrong. I never heard westerners named after Lou when I was in China, so I made the bold guess it's sex-neutral. But it's actually often used as a girl's name in France, and maybe in other western countries as well (I later found a song to prove this: Lewis OfMan - Hey Lou). By the time, I knew little about French culture and was quite disappointed upon realizing this fault.

Fortunately, Lou had been very much welcomed by our colleagues, although I didn't expected them, even after knowing the name, to call Lou a boy and use the pronouns he/him. Why? This question has been lingering in my mind until recently.

The word "robot" first appeared in a Czech play by Karel Capek at 19201 called R.U.R. ("Rossum's Universal Robots"). After the play debuted, it was translated into many European languages as well as English in just three or four years and became influential through 1920s into 1930s across the western world2. As to the gendered languages, at least for French, I can tell "le robot" inherit its gender directly from Czech, given that R.U.R. was translated by a Prague-born writer who studied in France3. And by reviewing the appearances of "robot" in the other gendered languages, it's interesting to find out it was treated as a masculine noun in all of them, such as the German word "der Roboter", Spanish "le robot", Italian "il robot", and Portuguese "o robô".

| Gender | Articles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Czech/Slovak | roboti (?) | mas. | ? |

| French | robot/s | mas. | le/les |

| German | Roboter | mas. | der/der |

| Italian | robot | mas. | il/i |

| Portuguese | robô/s | mas. | o/os |

| Spanish | robot/s | mas. | el/los |

The original Czech word literally means "forced labor". Not unexpectedly, most forced labors are males before more than 100 years ago. Proof? We can take a look into Capek's mind back then. According to Wikipedia4, there were 6 named robot characters in R.U.R., only two "robotesses" (Czech: robotů) while 4 "robots" (Czech: roboti). Although subtle, this bit of bias has been implicitly retained by the grammatical genders in Latin languages and German, potentially shaping our view of robots nowadays.

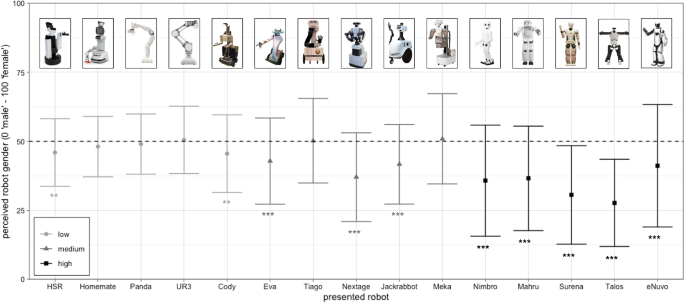

But that's not the whole story. In Capek's play, robots were divided into two sexes: robots and robotesses, with the later exactly referred to female robots. But "robotess" is not used any more, which rises an alert of the prejudice to classify robots as males, although this bias can be justified by the fact robots are mostly made by metals and with mechanic movements, which are associated with male workers more often. Recalling my previous post about the body images of social robots, people indeed perceive robots as males, regardless of the appearances, without exception5.

Should language limitations be blamed for misleading the way we view the world? Probably not. In a study that compared how the gender of robots is perceived by English and German speakers, the researchers didn't find a significantly larger male bias in speakers of the gendered language6. This result means the grammatical gender used to refer to robots in German didn't reinforce German speakers' male bias. The interplay between language and cognition may not be what we expected. The two systems don't magnify each other's bias toward robots; rather, it's our cognition that determines which word we would use to describe a robot.

Footnotes

Wikipedia in Czech: https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/R.U.R.

Li, B., Ajjaji, O., Gigandet, R., & Nazir, T. (2023). The body images of social robots. In , 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Its Social Impacts (ARSO) (pp. 1–8). : .

Roesler, E., Heuring, M., & Onnasch, L. (2023). (hu) man-like robots: the impact of anthropomorphism and language on perceived robot gender. International Journal of Social Robotics, (), 1–12.